This article originally appeared in the May 1993 issue of UltraRunning.

by Joe Oakes

Young Violetta looked puzzled, afraid. All of this attention bothered her. And she was tired. Violetta knew that Papa was doing something very special, but why did it have to involve her? Oh, how she would have preferred to have stayed at home with Mama. Still, this was for Papa, and she was ready to do anything to help him to reach his goal. Such a strange and difficult goal!

Every day the newspapers had reported just exactly what he was doing. Every day someone was predicting that Papa would quit, or become very sick, or maybe even die. But he didn’t. And he would not. Papa would never, never quit, not her Papa. And now she was ready to do what he had asked her to do. She would run with him on his 615th mile.

The Venice Vanguard very proudly said today that it would be a world record, set right here in Venice, California. Funny, but just the other day the same paper had used the word “freak” when talking about Papa and his running. Fickle! Violetta would be very glad when this was all over. She would run this mile with Papa because he had asked her to, and because he looked so piqued, and because she loved him so much. But she hoped he would never ask her to run again. Ladies did not run, and both she and Papa knew that.

The date was December 17, 1910. The place, Venice, California. Mr. Eugene Estoppey was in the process of breaking a formidable world record.

He had committed to run 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours. By simple mathematics, that comes to one mile per hour for 41 1/2 days. If you were to run at three miles an hour, you could do it in eight hours per day and finish up in the allotted 1,000 hours. That is about the limit pace for the Trans Am Race, and they run a lot further than 24 miles a day, and for a lot more days, too. Not such a big deal, that 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours.

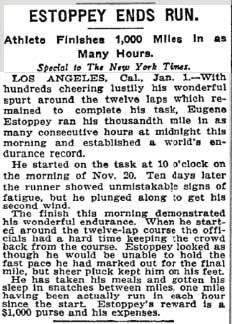

But wait just a minute. Look at this item from the Los Angeles Times a couple of weeks earlier: It says that Eugene Estoppey would, on a wager of $ 1,000, run 1,000 miles in each of 1,000 consecutive hours.

- A thousand dollars.

- A thousand miles.

- A thousand hours — every hour. When do you sleep?

While they have faded into the history books, all but unknown today, races at A-Mile-An-Hour were regularly contested in the early part of this century. The supermen who did these events were not like the famed pedestrians, the prototypes of today’s ultrarunners. No, they were milers. Every hour on the hour, they raced. They would take on all comers, sometimes winning, sometimes not, but always ready to go another mile in another hour. In December, 1910, the recognized world record in this event was 614 miles in 614 hours.

Going for the record

Eugene Estoppey had bet that at the beginning of every hour from November 20, 1910, until midnight, December 31, he would run a mile. So far he was making good on his promise. At the beginning of each and every hour he would get a quick rubdown, run his mile, get another rubdown, and pass the time until the next time the big hand got back to the 12.

Estoppey in his 316th mile. Venice, CA

For nourishment, he ate five times a day. While there is no record of what he ate, the papers said that he would refuse all food offerings except from trusted friends, a Mr. and Mrs. Fox. One can imagine that the gamblers might have loved the opportunity to add a little to his menu, considering the size of the wager, the times, and the potential for reaping a good profit from a bit of mild skulduggery in the form of food doctoring. No, he was very careful during this world-record attempt. He did tell the press that he appreciated the offers of food from the fine ladies of Venice, but he would prefer flowers.

The question began:

When and how much did he sleep? The L.A. Times tells us that he never took more than 35 minutes sleep at a stretch, and that his total sleep amounted to not much more than four hours a day in seven or more catnaps between runs.

Most of the time he sat around, rested, wrote letters, signed autographs, and did what it took to maintain a generally jovial and pleasant demeanor.

When he did put his head down to sleep he was always in the arms of Morpheus within three minutes.

Eugene Estoppey was a runner, and a very fine runner for his time. Keep in mind that Queen Victoria, that symbol of imperial greatness, was not yet a decade in her grave.

It would not be until mid-1914 that the Archduke Franz Ferdinand would catch the bullet of a crazed Serbian nationalist in Sarajevo, setting off a very ugly World War in Europe. Just 39 years before, Estoppey was born in Europe on April 12, 1871, in Lausanne, Switzerland. At the age of ten his parents migrated to America, and it was here that he learned to run.

How good a runner was he? His name isn’t on everyone’s tongue, and it isn’t clear that he was the best miler of his day. Still, he had a personal record of 4:40, and his hourly miles were done at a good pace. According to the papers, he reeled off the first of his hourly miles in 5:35, a respectable clocking in any time.

Let’s look at how the papers covered the event:

Venice Daily Vanguard, November 26: “ … completes 151 miles in six days … one leg weakening . .. freak race … on occasions when he feels especially gay, he covers the distance in well under six minutes.”

December 8: “Footsore Estoppey Yet Runs.” After 439 miles of dirt, asphalt, cement, boardwalk, and dance floor, Eugene Estoppey’s feet were sore. In the opinion of Doctor Le Fevre, who examines him twice daily, he would last no more than another 100 miles. (The betting picked up.)

December 11: “Rounding his 500th mile … hundreds of spectators.”

December 16: This was the day when 14-year-old Violetta would run a mile with her Papa. That mile, his 615th, would break the world record. Despite many attempts, no one had passed this barrier. It was said that previous failures were “mental,” not physical. Twice, it was reported, men had ended up in insane asylums after such an ordeal.

Estoppey was different. He was enjoying it. Until today he had “run hourly sprints against various beach runners,” racing every hour on the hour. This levity would now have to stop. He would now have to get serious. The world record was already his, to grow as far as he would carry it. Every hour, every mile, he drew closer and closer to that seemingly impossible goal of 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours.

An iron will, a sense of humor

Think about it. One mile per hour, every hour without stop. Food and rest have to be grabbed between runs, and your body has to do its best to put that food and rest to use in keeping the engine running. At what point does deep fatigue take over and shut the machine down? When does sleep deprivation become so severe that the body refuses to go on?

At first people thought it was weird, this oddball race. No one really expected him to be able to go very far. It all seemed to be just a lark. The discerning eye would, however, pick up a few clues. First, the wager. In 1910 1,000 smackers was a very large amount of money. The second clue would have been apparent only to the few with the ability to look deep into a man and size him up. He was very obviously a runner, but more so, he was a man of very strong motivation, a fellow with a positive attitude and a will of iron. He was confident.

To watch him run was to feel his spirit. As he got further into the event, the Los Angeles Times attributed his success to his ability to remain light-hearted while under apparent duress. He took good care of himself, eating well, resting as he could, and joking with those around him. He changed his running costume frequently, showing a preference for what he called his “stars and stripes outfit” and another emblazoned with the crest of his native Lausanne, Switzerland. He was as proud of his Swiss heritage as he was of his adopted America.

America had been good to him. In December of 1910 he was a 39-year-old family man, happy to be in California. Here in Venice, which was at that time almost as big in area as its neighbor, Los Angeles, he enjoyed a beautiful climate, crisp clean ocean air, and a good healthy lifestyle. And now, at almost 40 years of age, he was finally getting a chance at the recognition and fame he deserved. When he was done here on New Year’s Day, he would be a hero, known the world over as a great athlete, the first man ever to break the 1,000-mile barrier. If he could only stay with it.

And, of course, a little hype

It did not hurt that the merchants and land speculators in Venice, California, were backing him with logistics and publicity. Though today it is only a small part of the Los Angeles megalopolis, Venice was in 1910 a separate entity, a sparsely populated piece of beachfront. The area was hungry for new people. This run would help to get “The Venice of California” publicized worldwide. The gold rush of northern California was already a half century into the history books. The railroads were now offering good and regular service across the continent.

The land speculators were anxious to tell the tale of their little piece of Paradise to anyone with a few loose dollars and a yen to travel. “Come West, young man,” they shouted. The phenomenon of Hollywood was just a few years over the horizon, with untold millions of dollars to be made, and millions of souls yet to pour in to this great Los Angeles basin. If only they had known!

With stiff leather shoes and sore feet, Estoppey ran on. Every hour his rubdown of olive oil, alcohol, and wintergreen readied him for another mile, another addition to his new personal property, the world record. On December 19, the Times reported that, “a good-sized crowd had gathered at the dance hall” where he ran at night, it had been a rainy day, but he had run his 700th mile at noon, and now at night he was reported to be in good spirits, even confident. They were amazed that he had gained a pound since embarking on this trial.

The next day would mark one month that Eugene Estoppey had been running; one mile per hour, every hour for a month without missing a single one. Every hour, every mile, his world record became even greater, that much more difficult for future challengers. And every mile Estoppey became that much more confident of his ability to meet his goal of 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours. On December 20 he sent a postcard to a friend:

“Dear Theodore,

Many thanks for the your Xmas card and wish you the same. Go to the limit on your betting. Can’t fail.” — Gene

“P.S. Come and see me finish the 1,000th mile, please.”

He was strong and confident, and he was urging his friends to place more money on him. “Can’t fail.”

On to 1,000 miles

What the newspapers had called a freak event a few weeks before now became a cause célébre. The excitement of this great run was infectious. The Los Angeles Times was giving him more coverage, including photos of him running, sleeping, and eating: “Every hour between 8:00 p.m. and 7:00 a.m. the night patrolman at the beach town comes around to the little room in the hall where he sleeps, wakes him, and keeps time and the number of laps (at) the dance hall where he has a 12-lap track measured off… His muscles and spirits are in the best of shape. It seems likely that he will be able to accomplish the feat… He is eating pies and cakes and a number of dishes that an athletic coach would declare unfit for a man in training.”

The next day the headline read, “No Faltering: Estoppey in Fine Condition,” and it told about prizes which were growing in number every day: “The Police Gazette has offered a valuable gold medal, and a number of his friends who had enough confidence in him to place bets (early) at the big odds which were offered are contributing liberally to the fund of prize money.” They then reported him running a 4:20 mile, “which is a coast record.”

On December 31, 1910, a large ad appeared in the Times inviting southern Californians to come to the Venice Pavilion, where “Estoppey will run the Last Mile in his 1,000-mile Endurance Contest at Midnight.”

The next day, January 1, 1911, the Times carried the following article:

He had done it. He had bettered the world record by more than 50 percent. He had been the first, and maybe the only, man ever to run 1,000 miles in each of 1,000 consecutive hours. After more than 40 consecutive days of performing every hour on the hour, Eugene Estoppey was bone weary. What part of his body did not hurt, what cell of his body was not screaming for rest?

Violetta said, “Papa, you must come home and rest now. You need a good sleep.” “Not yet, my darling daughter. In the morning I must run one more mile for $200 in Pasadena at the Tournament of Roses. Then I will rest.”

Footnotes

Several notes of interest:

• The Tournament of Roses in those years involved chariot races, not football games. Football had been banned by the Tournament officials because of rioting at a previous tournament.

• The papers often stated that Estoppey ran just over a marathon per day. A “marathon” in those days must have been some distance under 24 miles. Does anyone know the distance?

• Thanks to ultrarunner and historian Harvey Schwartz for his original articles and correspondences regarding Eugene Estoppey. Thanks also to Chris Oakes and John Mustain for research work.

• Finally, a bit of a disclaimer might be in order. Peter Lovesey reported in the October, 1989, issue of Ultrarunning that several people, including some women, had done 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours, and, indeed, even more difficult feats of a similar nature, both in the U.S. and in Great Britain.

There is one big difference, though. All of the reports of these 19th century athletes state that they walked their distances, while Estoppey ran his miles, some of them quite fast.

We have only the printed record to guide us. I, for one, am willing to accept the reports as they stand, giving Estoppey his somewhat obscure place in the history books. Still, the element of real estate hype and gambling puts my judgement in a state where I would not be at all surprised by the revelation of a bit of skulduggery.

I suppose that we will only know when we get to the pearly gates.

1 comment

Question in the text: The papers often stated that Estoppey ran just over a marathon per day. A “marathon” in those days must have been some distance under 24 miles. Does anyone know the distance?

Answer from Wikipedia, widely reported elsewhere: “The International Olympic Committee agreed in 1907 that the distance for the 1908 London Olympic marathon would be about 25 miles or 40 kilometres. The organisers decided on a course of 26 miles from the start at Windsor Castle to the royal entrance to the White City Stadium, followed by a lap (586 yards 2 feet; 536 m) of the track, finishing in front of the Royal Box. The course was later altered to use a different entrance to the stadium, followed by a partial lap of 385 yards to the same finish. The modern 42.195 kilometres (26.219 mi) standard distance for the marathon was set by the International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF) in May 1921 directly from the length used at the 1908 Summer Olympics in London.”

Highly recommended, for those interested in the period: “Showdown at Shepherd’s Bush”, by David Davis. About the 1908 Olympic marathon and the build-up and competitors. Also terrific is “The Celebrated Captain Barclay : Sport, Gambling and Adventure in Regency Times” by Peter Radford.

Comments are closed.