The father had always been old school and a bit old-fashioned. He was a man who could easily handle both a stethoscope and a shotgun, his life shaped by time tending patients in emergency rooms in Roseville, California, and in caring for horse riders, and then for runners, on the Western States Trail.

He was considered to be a medical practitioner with a surprisingly mystical bent. It was said he could look into the eyes of Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run participants and tell instantly if they were destined to fail or finish.

“You look into their eyes,” he said on more than occasion, “and see if the soul is separating from the body.”

When the news came on December 6, 2014, that his son had been chosen in the lottery to run at Western States, the outlook for the father was not good.

A 16-year battle with metastatic prostate cancer had seen the cancer gain the upper hand. At 81, and having been a part of Western States since its inception in 1974, it wasn’t clear if Dr. Robert Lind, medical director emeritus for Western States, would see another rendition of the world’s oldest 100-mile trail run.

“We didn’t know if we could expect that my father would be there in June to see the start,” said Lind’s son, Paul. “He’s an old-school doctor. He knows how these things tend to go. But we knew if there was one thing that was going to motivate him to do all he could do to get to June, it was Western States.”

Even before he finished the race for the first time, at age 18 in 1986, Western States had gripped Paul Lind’s imagination. He was 7 in 1974 when his father, the medical director for the Tevis Cup, brought Paul to watch the annual 100-mile horse ride, held on the Western States Trail. A good friend of the Lind family, Gordy Ainsleigh, made history that day. Ainsleigh ran, rather than rode, the entire 100 miles in under 24 hours.

“I was probably more interested in the horses, to tell you the truth,” says Paul. He lives in Challis, ID, where he coaches high school cross country and track. “But you know … I loved what I saw and experienced. I loved being out on the Trail, being with my brother and my Dad.”

Paul remembers being ten, and sleeping out with his family at White Oak Flat, one of the race’s historic checkpoints. He can recall the family dinner table strewn with 20 blue and white t-shirts with the WS 100 logo printed on the front, and his father wondering if there were enough people in the world willing to buy t-shirts for an obscure 100-mile run.

And then there was the shotgun. Bob Lind had grown up on a farm in Iowa. He had taught his sons, Paul and Kurt, to safely handle the family’s single-shot, 20-gauge shotgun. Before every Western States, Bob Lind would take two shotgun shells. With the precision of a jeweler, he’d carefully stencil on the shell’s casing the inscription “WS 100” followed by the date of that year’s run.

When 5 a.m. and race morning would arrive, Bob Lind would discharge his shotgun into the chilled Squaw Valley air, sending the runners officially off.

“Starting a race like Western States with a whistle or a horn just wasn’t appropriate,” Paul says. “You need to start a race like Western States in a special way. It’s a very sacred thing.”

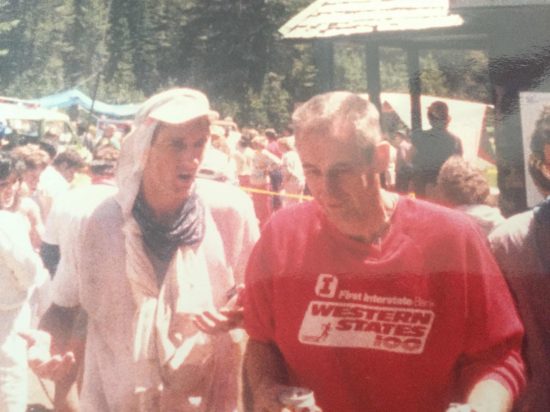

Bob Lind, as scores of runners discovered, was more than a smiling, hawk-nosed man whose white hair, no matter the circumstance, always seemed to neatly gather in a distinguished widow’s peak. Lind’s medical work at Western States laid the groundwork for influential research studies that forever changed the sport.

“Bob Lind was incredibly generous in his support and encouragement of medical researchers from throughout the world,” said Dr. Walter Bortz of Stanford University, who did a seminal heart study of Western States runners in the early 1980s. “I think Bob understood what an amazing outdoor laboratory Western States provided us.”

As the race crept closer, Paul Lind traveled often from Idaho to train on weekends on the Western States Trail. Once training was over, he’d drive to nearby Roseville to visit his father. Bob would ask, “Did you stay ahead on your fluids? … What did you weigh before you ran? … What did you weigh after?”

Paul could tell his father was not just gathering data. Bob was gathering himself… for June.

“Dad fought harder and focused in on everything he needed to do, to get to Squaw,” Paul says. “This race is our family’s tradition.”

Paul slept in a motor home in the parking lot of Squaw and woke to a warm race morning. His son, Cody, 20, a student at Idaho State and a rising talent, would be Paul’s pacer. Kurt had woken Bob at 2 a.m. The two had driven in darkness from Roseville to Squaw. Bob walked unevenly from the parking lot to the starting line. A couple of times he needed Kurt’s help.

On this morning, though, Bob wasn’t going to be deterred.

“I think you could’ve put that start five miles away, and my dad would’ve walked it,” Paul says. “He wasn’t going to miss the start.”

Nor was Paul going to miss Bob’s big moment.

“When my old man was standing there, with the shotgun, ready to start the race, I didn’t care what it looked like for me to be way up in front with the elite racers,” Paul says. “I was going to stand right with him for that sacred moment.”

“My reasons for running were far different than most,” he adds. “It had been a long time since I’d run the race. I probably got emotional because it would more than likely be the last time we’d share the experience. There is no more magical ground than that trail.” Paul wanted to make his father proud. He wanted a silver buckle.

The race itself unfolded as most races do: in its own way. Paul ran methodically, monitoring his effort. He was mindful not to overexert in the early miles. He was careful not to panic, his soul remaining firmly planted in his body, even as he fell behind 24-hour pace. As his father advised, he kept the fuel and fluids coming regularly. Paul constantly doused himself with ice water.

“Each time I’d ice down, that was Dad, that was Dad telling me to manage the heat,” he says. But it was much hotter than usual in the high country, and the heat, mountains and challenging trail exacted a toll on Paul.

When Cody joined his father in Foresthill, 45 minutes off 24-hour pace, the race was just beginning. The miles passed, and Paul’s pace increased. He spied friends at aid stations and rekindled friendships, remembering ghosts and spirits of Western States past, the runs and rides he’d attended as a boy, crewed and paced as a man. They were all moving with him through the night.

By No Hands Bridge, with three miles to go, Paul was now one minute ahead of 24-hour pace.

“First time all day I was ahead of 24-hour pace,” he says.

Running with his son along the quiet, flat road below Robie Point, where the air often becomes heavy, and the trail can often sound fret-scratched and anxious, Paul slowed.

He asked Cody for his cell phone.

His father had been at home, receiving updates in the same calm, analytical way that he would receive reports while heading the emergency room at the community hospital in Roseville.

“Dad?” Paul called into the cell phone, worried about the spotty coverage.

“Son?” asked the 81-year-old voice on the other end, sounding surprisingly resilient.

“We’re cutting it close,” Paul said. “But I think we can do it.”

“One more hill,” said the voice on the other end, sharp and suddenly imperative. ”One more hill. And then you’re finished.”

Paul would finish in 23:52 and earn a silver buckle.

His father, a man who had looked into the souls of thousands of runners over the years at Western States and who knew who was destined to succeed, knew exactly what kind of race his son had run.