By: Renee Despres

When El Paso ultrarunner Steve Silver called to ask me if I wanted to accompany him to Copper Canyon to run with the Tarahumara Indians, I have to admit that I paused a second. I had never met Steve, although we had spoken on the phone a couple of times. And here he was asking me to take off for a weekend in Mexico with him?

Steve explained the situation. Jerry Davis, the president of his track club. The Half-Fast Runners of El Paso, had asked him to travel to Copper Canyon to participate in the Primer Ultra-Maraton Reto Tarahumara, the first open-invitation race in the Tarahumara’s native land. Rick Fisher was the race director. Steve assured me that he was happily married, his wife couldn’t go because of other commitments, and he wanted someone with him to brave the logistics of travelling in a foreign country.

Steve couldn’t give me much information beyond the fact that the Tarahumara would compete in a traditional kickball race on Saturday, and that the open race would take place on Sunday. Both races were supposed to start in Divisadero, about thirty miles south of Creel, Chihuahua. Silver wasn’t sure what sort of distance the open race would cover, but had heard that it would be somewhere in the range of 100 kilometers, plus or minus a crawl into and out of the canyon. Aid stations were promised, with oranges, bananas, pinole (finely ground corn meal mixed with cold water; the Tarahumara water it down and use it as their sports drink), and water. Whether the water would be bottled or not, he couldn’t say.

I spoke with my neighbors, Jane and Dean Bruemmcr, true Copper Canyon aficionados. They’ve hiked and canyoneered through more areas of Copper Canyon country than most gringos know exist. They’ve found themselves in caves, cliffs, floodwa-lers, heal, and marijuana fields (at which point they got their butts out of there faster than you can say “joint”).

“I have no idea where you’ll be able to run there,” said Dean. “It’s steep, wild country. And it’s easy to get lost out there, because there are goat trails going off in every direction.”

You have to understand that I’m notorious around my home in the Gila Wilderness in New Mexico for my ability to fall down — even my non-running neighbors usually check my elbows and knees for the marks of the most recent tumble. If Dean said this was tough country, I believed him. Dean has worked on hotshot crews and Search and Rescue teams around the western United States. I’ve seen him scramble up rocks that would faze your average mountain goat, all the while carrying a 50-pound pack.

I told Steve I’d go. Jane and Dean were also interested in coming along.

Why in the world would I want to go to an event that I knew next to nothing about, that was almost certain to be unorganized, and that I was guaranteed to be really lousy at? I liked the nebulous nature of the whole affair. Dean’s and Jane’s talcs of Copper Canyon had always intrigued me. And finally, there has been so much ugliness and controversy surrounding the Tarahumara’s entry into the American ultrarunning scene that I wanted to see what would happen when the tables were turned, and I was the stranger in the strange land. So perhaps I believed that I could enact a bit of diplomacy, for I wanted to go down with goodwill and an open mind. And I will admit to a bit of curiosity — I wanted to see how Rick Fisher operated on the terrain he has claimed as his own — Tarahumara land.

It was a motley crew that walked across the bridge from El Paso to Juarez, Mexico. Steve Silver is a former New Yorker who sports a short pony-tail that matches his last name in color. He’s a confirmed trail runner who also enjoys the offerings of a city. Jane and Dean Bruemmer, like myself, arc confirmed grunges. We’re happiest when we’ve been camping for five days without a shower. Jane confessed that they usually end up getting searched by the Federalis at least once on each trip to Mexico. Our group of five was completed by Sacramento-area ultrarunner Richard Jones. His steady cheerfulness would end up being a boon to the whole trip.

We took the bus from Juarez to Chihuahua City, a long but not terribly unpleasant trip that included only a few Federali stops and the occasional onboard vendor.

We not-too-regretfully turned down a copy of a book filled with Aztec medicinal secrets, despite one vendor’s practiced fifteen-minute oration in fast Spanish.

In Chihuahua City we found a strange mixture of wealth, poverty, city-style rush, and Mexico-style siesta breaks. And we also found some heartening news — Steve asked at the tourist bureau and discovered that they had indeed heard of a race that was supposed to take place in Copper Canyon that weekend. Yes, they told him — the race goes into and out of the canyon. Oh, great, I thought. Jane’s earliest description of Copper Canyon rang in my mind — something about it being deeper than the Grand Canyon, and very easy to get lost in.

We rented a car in Chihuahua City and continued on to Creel the next day. The car, a Chevrolet Cavalier, would have comfortably seated four people. With five people plus stuff, it felt more like we were doing the Volkswagen cram. So when, after spending four hours in the back seat getting a little too closely acquainted, we finally arrived in Creel early in the afternoon, and weren’t too enthused about driving another hour-plus down to Divisadero.

Creel is the tourist center of Copper Canyon country. It’s the place where all those headed into the backcountry gather to stock up on supplies, sleep a night with a roof over their heads, and exchange stories and information about the largely uncharted territories they’re headed off to explore. A tiny little village by American standards. Creel is dotted with hotels. Upper-end hotels like La Cascada, where the manager is almost certain to speak at least some English, cater to less adventurous tourists. Rooms are clean and still cheap, coming to about $40 a night for a double. At Margarita’s, you can get a dorm room, breakfast, and dinner for the equivalent in pesos of less than $5 a night. Over the dinner table you’re sure to find out all the local news.

Unfortunately, Margarita’s reservation policy is about the same as her price range. We had reserved a couple of rooms, but arrived to discover that Margarita was sick in bed and had rented out our room to someone else. Luckily, Steve had also made reservations at La Cascada, so we all piled into two rooms there until some space opened up at Margarita’s the next night.

“That’s travelling in Mexico,” said Jane, shrugging her shoulders.

Creel is also the place to find out what’s going on in Copper Canyon country. Steve, ever the detective, managed to find out more about the run and save us the drive to Divisadero. He went to the Tarahumara Mission and emerged with a flyer that described the events. The kick-ball race was supposed to be taking place that afternoon, from 1:00 until 8:00 in the evening. But according to some tourists who had just returned from Divisadero by train, nothing was happening down there. There had been some dispute amongst the Tarahumara teams, and one had pulled out.

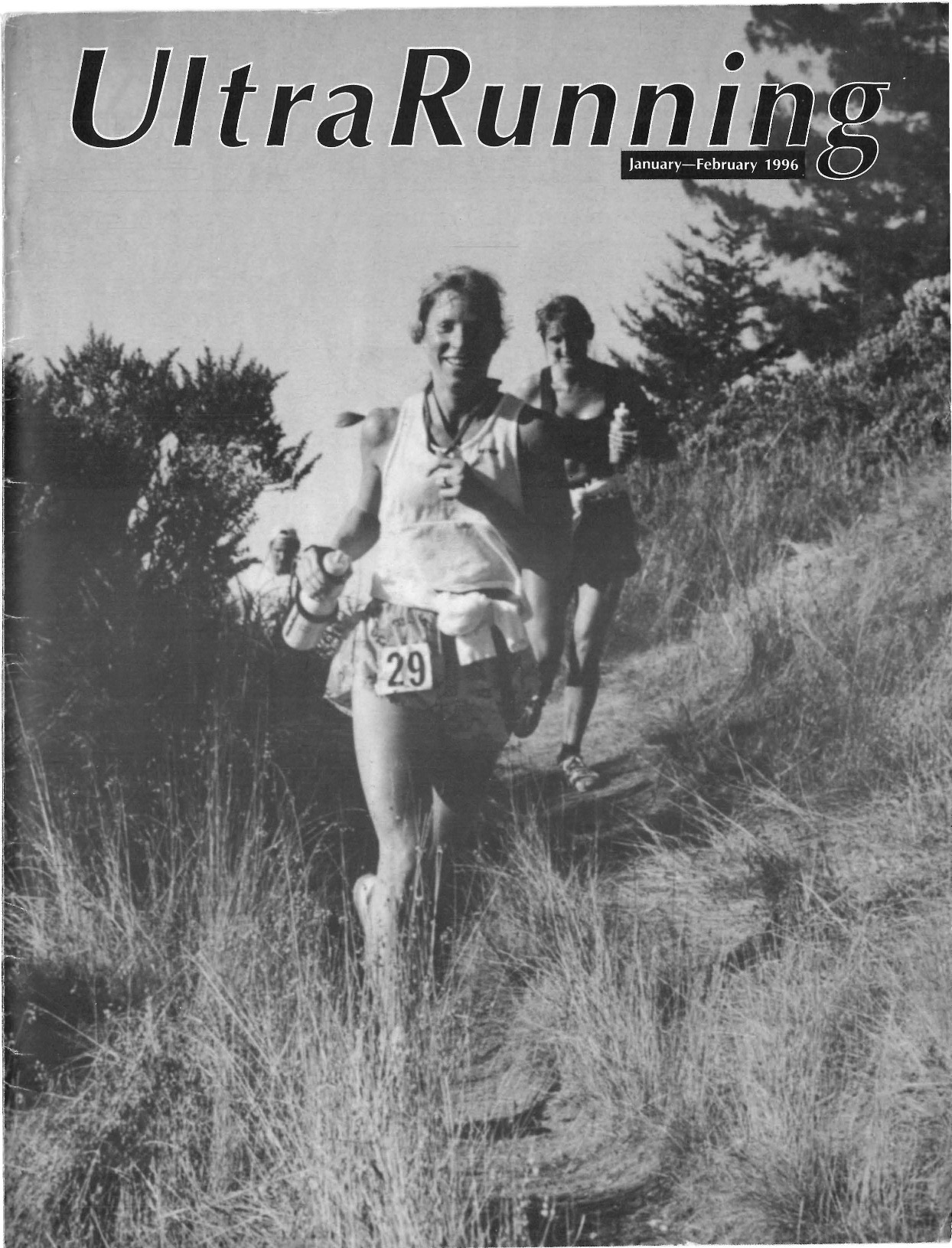

The starting line in Areponapuchic: The Tarahumara in the center, including the eventual winner Gabriel Bautista (#46), flanked by the U.S. runners Renee Despres (left, #38), Micah True (right, #40), and Steven Silver (far right). The starting line was a piece of twine across the road.

The flyer also contained some information about the open race. It was scheduled from 9:00 a.m. until 5:00 p.m. the following day. To us gringos, that seemed to mean that we were going to run for eight hours and call it a day.

I breathed a sigh of relief. I hadn’t exactly trained for this race, the whole ten days notice that I’d had not leaving a whole lot of time for long runs. The shorter the race was, the better off I would be, and there was no way I could cover 100 kilometers in eight hours on that sort of terrain. Steve, on the other hand, was somewhere between ecstatic and disappointed. An eight-hour run? He’d just be getting warmed up.

Still a little bewildered, but comforted to have an actual piece of paper saying that the race wasn’t just a figment of our imaginations, we turned in for a night’s sleep.

We arose at 5:30 a.m., managed to cram ourselves into the ear and headed up the road by 6:00 only to be stopped by a Federali of none-too-friendly mien. Once again, Jane’s gracious smile and fluent Spanish got us out of a tight spot.

But we still didn’t know exactly where we were headed. Everybody we had talked to while in the States had told us that the race would take place in Divisadero. But the poster that accompanied the flyer listed Arcponapuchic, an even smaller village, as the race headquarters. So we left early, uncertain as to whether the event would even take place. Whether the kickball race had happened, we still didn’t know.

As we drove through Divisadero, we saw no sign of anyone resembling a runner. A few Tarahumara women in their bright skirts walked about, but otherwise the streets were deserted. Only one thing indicated that there might be a race in the vicinity: a bright blue port-a-potty was stationed next to the park, across the street from the Hotel Divisadero. It looking brightly out of place in the dark brown wooden structures of Divisadero.

Areponapuchic was only a couple miles further down the road, so we decided to drive onwards and sec if there was any sign of life in that area. It was about 8:00, an hour before the race was scheduled to start, so we figured there would be some sort of hubbub at the headquarters.

In Arcponapuchic, no one was about except for a few local Mexican men who were hanging out near the town store. But we knew we were getting closer when we discovered, not one, but six bright blue porta-potties next to an open-air church. A few queries finally yielded some information: yes, the race was supposed to happen; yes, it was supposed to happen at 9:00 a.m.; and yes, the church was the headquarters. The runners were keeping warm in a hotel up the road. The course, said our informant, Sonja Estrada Morales, a young, friendly, and professional woman from the Chihuahua tourist bureau, was well marked and easy to follow. It dropped about 2,000 feet into the canyon, which meant that there was a corresponding 2,000-foot climb out of the canyon. The race would consist of four laps, each about 20 kilometers in length. She gestured toward a nearby trailhead.

Whew. I was so happy I sat down and chugged a can of Ensure Plus. Only half an hour until the start.

Well, half an hour Mexican time. Around 9:10 or so, Rick Fisher drove up in a van full of Tarahumara runners. One other gringo appeared dressed in running clothes: Micah True, a Boulder, Colorado, ultra-runner who spends his winters in South America. Micah had run with the Tarahumara once before and was eager to take part in this race. He had run the course the day before (he pointed in a direction opposite to the one Sonja had pointed in), and said it was very difficult to follow. They hadn’t been planning to mark it, but he had suggested that it be marked after yesterday’s run. But he didn’t know what sort of markings would be used.

Hmm.. .

Eventually, we started to assemble for the start. The field consisted of 19 Tarahumara Indians, Steve, Micah, and myself. There were a few moments of awkwardness when the Tarahumara realized that I, too, intended to run — gringos were bad enough, but I was a gringa. They seemed a bit relieved, however, when I pantomimed my standard running speed in comparison to Ann Trason’s and the net effect was something like comparing a turtle to a Lear jet.

Fisher called us up individually, his photographic instincts determining the order in which we were called. We spread out across the less-than-two-lane dirt road, all managing to get on the front line. A few tourists squeezed in for a chance to get their picture taken. Tourist cameras and two film crews, one from Los Mochis and the other from the Australian airlines Qantas, went to work, and I must admit I felt a little silly. I hadn’t really checked that morning to see if it was a bad hair day.

The picture-taking was interrupted briefly by the arrival of an army truck — just some Mexican military on the way down to investigate the local marijuana fields. We scattered off the line and then resumed formation. Fisher came up to me and gave me a few more tidbits of information. There would be no potable water at the bottom of the canyon, the course was marked with red material, and don’t get in trouble because there’s no Search and Rescue here. I received his words of advice with gratitude.

He turned to the rest of the field and, through Sonja’s interpretation, dictated the bare facts about the course: it was about 20 kilometers in length, it involved a little ridge running at the beginning, then a descent into the canyon and a steeper climb out. Runners had to give their numbers both at Divisadero and at headquarters. The first person to complete four laps of the course was the winner. If any runners felt that they couldn’t complete the fourth lap before dark, they were to withdraw after the third lap.

Voices started chattering in tarahumara, and we gringos looked about, a bit confused. Some of the Tarahumara runners held up three fingers. Sonja exchanged a few words with them, then translated for Fisher. He shrugged his shoulders.

“Okay,” he said. “The race will be three laps.”

Finally, about 10:00 a.m., Sonja fired a starting gun and the whole field took off running. The frontrunners (don’t ask me what Steve and I were doing with them) headed up the road about 100 yards and veered to the right — only to hear shouts behind us. Wrong turn. We were supposed to have continued straight.

This does not bode well, I thought to myself as the rest of the field, including Steve, ran off ahead of me. I had run with the Tarahumara Indians in their own land — for a whole quarter of a mile.

Good. I could relax and enjoy the view, for this was truly some of the most spectacular land I’d ever seen, and I’d brought my camera along to record what I could. So I trotted along, trying to follow the assorted pieces of red cloth that marked the trail, pausing at intersections to look for the telltale sign of gringo footprints. The marks from Steve’s Asics Gel-Moros stood out like a knobby tire amongst the Firestones and Goodyears of the Tarahumara’s huarache prints.

The red course markings were abundant for a while — and then, just as the descent into the canyon began, they stopped.

Chicken-footed, I made my way slowly down into the canyon. The sharp, loose rocks and steep descent could have turned ugly very quickly. I kept looking for a reassuring red flag to tell me that I was going the right way, but they seemed to have disappeared. The footprints continued, though, so I kept slipping and sliding my way down.

Just about where things began to level out again, I saw Steve — headed my direction. He had run about a mile further up the trail and hadn’t found any markings, although there were, as Dean had promised, lots of trails to choose from. We had figured out how to get down, but getting back up was a bit of a problem.

Bummed, we turned around and hiked and ran back up to the start, where we found Sonja and told her that we were dropping out and raided the gringo aid station in the trunk of the Chevalier. Not knowing what to expect, I had packed a Norm Klein-style aid station, complete with Gatoradc, a couple varieties of cookies, PowerBars, soup, Pepsi, Pop-tarts, and hard candies. We had bought bottled water in Creel before the race.

So we munched for a while while Richard, who hadn’t planned to run in the race but wanted to see what the course was like, got his running clothes on and ran a mile up the road to tell Jane and Dean what was up. When he got back, the three of us (Richard and Steve and I) headed off down the trail again.

And then something incredible happened — I started having fun. I mean real, true, stress-free fun. We trotted down to the place where Steve had turned around before, looked around the next bend, and found a piece of red material that directed us across a dry creekbed. Too little, too late, but there were three of us and we were determined to find the right route now that we knew that it was indeed marked. We climbed up a few drainages and side canyons before finally finding the right one — easy enough when the Tarahumara leaders passed through on their third lap. That’s when we discovered that, yes, we were supposed to do that vertical climb up the rock face. We’re talking hand-assisted “running” here. The Tarahu-maras who had voted for three laps must have known the course.

We stopped for a few Kodak moments, hoping to capture some of the exhilaration and beauty of that climb. I shall have to work very hard, harder than I worked at any moment during the climb, to find any words that could come close to describing it. But at that moment Copper Canyon offered something more than the sharp colors of the Grand Canyon, the largeness of the Sierra Nevadas, or even the deep plunges of my home in the Gila Wilderness. And I suddenly understood why Jane’s and Dean’s eyes light up every time they mention Copper Canyon.

We found our way (it was easy after that: just go up), finished our one lap, and returned to find the awards ceremony in progress. The first finisher, Gabriel Bautista, ran three laps in 5:32 — less than the time it took us confused gringos to complete our lap and a half. The second finisher was 17 seconds behind him. Micah, the other crazy gringo, finished the race in seventh place. Fisher distributed trophies, money (which came from the Chihuahuan government), and other prizes. Joe Herbert, Bruce Kasiler, and Chris Pratt, three gringo spectators, had brought down an assortment of blankets, food, and other gifts from Salt Lake City, which were also distributed. After four years of drought, the Tarahumara supplies of food and clothing are in short supply.

I know that I’ve not truly addressed the question foremost in the mind of any ultrarunner who has been following Rick Fisher’s antics at Western States, Wasatch, Leadville, and the other American ultras where he has acted as the Tarahumara’s team manager. I will say this: that Fisher was generally gracious and friendly to the gringos present, a side that he has not shown the ultrarunning community when he has travelled northward. I don’t know if he’s doing the right things for the wrong reasons, or the wrong things for the right reasons, or perhaps a little of both. He made sure that his benevolence was recorded on film. Was it a show for the benefit of the gringos present? Probably. But the Tarahumara who ran this race received more than a handshake for coming in first or second; these were awards that they could take home to their villages to help feed hungry mouths and warm chilled bodies.

So it was with mixed feelings that we finally drove away. And it is with mixed feelings that I write this piece about running in Tarahumara land, for part of me wants to keep it a secret, to keep it all to myself. The Tarahumara are a gentle, shy people who live in one of the most untamed places on this earth. There was something very special about the smallness of the race, and I feel honored that the Tarahumara accepted me and my fellow gringos as a runner in their land.

Steven Silver adds:

Imagine taking a trip to run a race in another country, when you don’t speak either of the languages, you have no idea what the course will be, how long the race is, when, or where it starts, if the trail is marked or not, if there will be aid, or what that aid will be.

This was an “ultra-different” ultra. I can’t quite decide what to call it — race, run, event — because it was more than a running experience for me and for those who joined me. It was more like living someone else’s life for a few days.

Those who know me would probably be surprised that I even considered taking this trip. After all, running through Copper Canyon without any concept of where I am going, what or who I am going to find at the end of the trail, following sheer rock and boulders “competing” with the greatest trail runners in the world, is not my usual idea of fun. But not only did I do it, I loved it.

I loved it because it was truly different. It wasn’t a hyped-up grand-slam event, with pressure to “buckle” or to set a personal record. It was simply an opportunity to run in one of the most awesome locations in this hemisphere, with (surely not against) athletes whose very being is running.

We still weren’t sure how long the race was, nor, as it turned out, was anybody else. When Race Director Rick Fisher, during his starting-line race briefing, got around to the number of laps we were supposed to run, a few of the Tarahumara objected to the planned four laps and said they wanted to run three. So, as Renee and I stood dumbly by, the final logistics of the race were set.

The gun went off, and we all went out pretty fast. Some of us headed straight and some of us veered to the right. Ren6e and I were, of course, in the latter group. It took me a few minutes to catch up with everybody. I was able to hold on for about three miles of the first 11-mile loop, but then I stopped to follow the call of nature and watched the last of the group run away from me. I lost the trail a few miles later and decided to return to the start. I met Ren6e on the way up and we both decided that good judgment told us to go home so we would not have to risk having Copper Canyon as our new home address.

After offering some complaints about the lack of trail markings, we decided to try again. Richard joined us, and the three of us headed off to run the loop. We got down to the spot where I had turned around, proceeded another 200 meters, and discovered a couple of trail markers. We followed these across a river bed until we got lost again. Finally, we saw the lead Tarahumara runners going the right way (opposite from the direction we were headed), and backtracked. We followed their path — note I said their path, not a path — and crossed fields, clambered over sheer rock and boulders, and discovered very little defined trail. Some time later, we hit the top of the canyon and ran back to the start/finish line. We refueled and hung out, having a great old time.

The awards ceremonies were unlike any I have ever seen. The first four finishers (the awards went four deep, sorry folks, no age-group awards) modestly and shyly rose for their awards, and smiled as they received rice, beans, clothing, and ceramic pots.

We learned something at that race. We learned that while we run for fun, for our egos, or for glory, the Tarahumara run to survive. In this 33-mile race, there was a 17-second difference between first and second place. Those 17 seconds cost the second-place finisher 500 pesos (about $67), a large sum.

And now I must say a few words about Rick Fisher. Rick has taken a great deal of criticism over the years for making demands on ultra race directors in the U.S. I will not address any of that, because I have not been there to see first-hand whether the criticism is justified or not. But I was at Copper Canyon, and I can tell you this: if it weren’t for Rick, I would not have had the chance to participate in this event. None of our group would have been there; Qantas Airlines would not have filmed the race; and the Tarahumara would not have run at Lead-villc, at Western States, or at Wasatch. They would not have been featured in People or in Outside. And there would be less com and beans on Tarahumara dinner plates, fewer huaraches on their feet.

Some would say that it would be better had the American ultrarunning world never heard of the Tarahumara. Some would say that someone else would have come to their aid if Rick hadn’t. Maybe so, but nobody has. Any volunteers out there? Rick and his wife Kitty are doing something nobody else has done — working with the Tarahumara. Be it for money, ego, power, or any other reasons, I don’t care.

As the great Jewish scholar Hillel once said, “If not him, who? And if not now, when?”